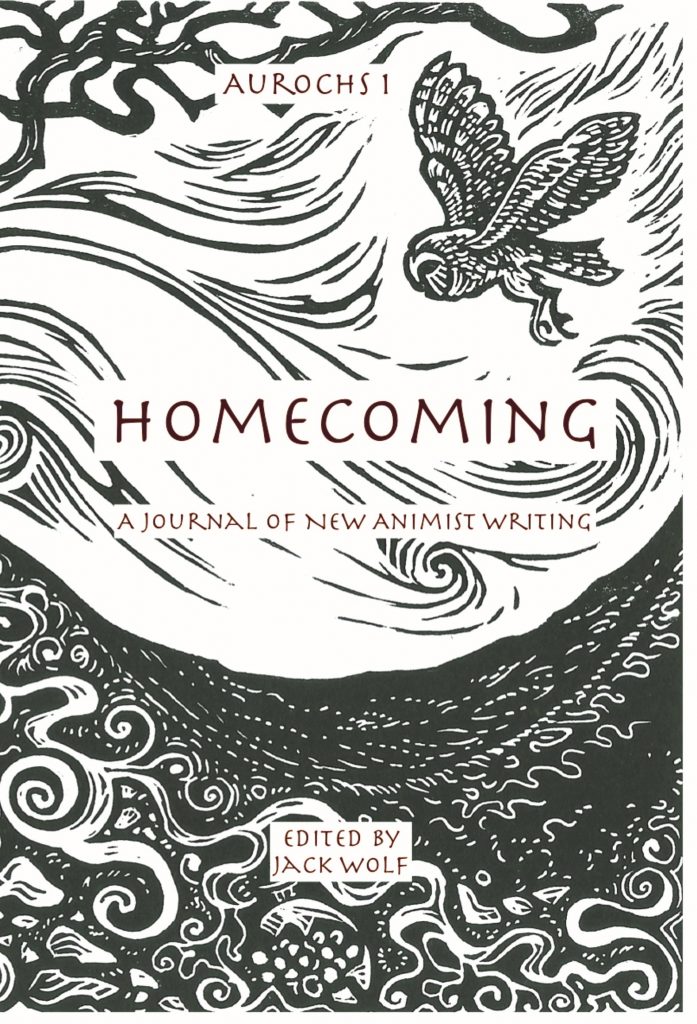

Additional Online Pieces

Issue 3: TIME

Time is a Deciduous Tree

Time is a deciduous tree.

Calendar to the seasons,

with no dates in a diary.

Time falls to the ground.

Layering memories,

Like leaves, one atop another.

Time flies.

But trees stand in testament,

of, with, and against time.

Alison Elliott

ISSUE 2: KINSHIP

This gorgeous poem by Quinn Colomba Boyko speaks about how a human being can enter into relationship with a river.

My Sister

The water is my sister.

She was always there as I grew up.

She played with me and my mother

and brother and dad,

endlessly interesting

and versatile.

I was warned to respect her,

so we always got along.

She was a great comfort

during prepubescent angst.

In the cold

I sat beside her on the dock

or rocks

watching

watching

watching

waves;

her speech soothing,

lilting,

lulling.

She always knew how to make me feel better.

As I grew,

she was privy to many a tete-a-tete

as I tread water,

talking the hours away

with a confidante.

If it was summer

and my suit was dry,

something was wrong.

I know her differently now.

How I missed her as an adult,

relocating from spring-fed sources

to rivers begun as glaciers!

Our relationship changed.

How can you revel together as before

when she has become so cold?

But I am drawn,

soothed still by the very sight of her.

Longing for our old ways together,

one winter I practiced taking icy indoor showers!

That summer I dared the frigid floes

to find something of the embrace

of my once constant companion.

The discomfort was worth it!

It is different,

but I reconnected with my sister,

the water.

She is part of my life

once more,

lifting and enlivening

long-forgotten places in me,

and I am so grateful.

@ladyquinn.writer (instagram)

LadyQuinn.enchantress.earth. (Author site)

***

Earth Mother Nature Lover is a poet, blogger, writer and nature photographer following an eclectic pagan path. In this piece, she remembers some early relationships with Other than Human Beings.

Memories of Trees

I have always loved trees. They have always featured largely in my life and this last year I have been really thinking about the trees I have encountered over the years and decided to write a poem about each of them as my way of honouring their presence.

As I’ve been remembering them and how I encountered them it has also brought back memories of people, many of whom are no longer with us. I feel that in honouring the trees I am also honouring not just loved ones gone, but also the ancestors. Many of the trees I’ve known were here long before us and some will be here after us too but for now I thought I’d share my memories of a few of the trees I’ve known.

My first encounter with a tree wasn’t the best experience. She was a Laburnum and rather beautiful. She stood in the border of the lawn and her cascades of golden flowers brought glorious colour to the garden in early summer. At the age of four I thought it would be a good idea to eat the seeds from the laburnum pods which resulted in a trip to the Accident and Emergency departs and my stomach pumped out. My father cut her down after this, which was a shame but I understood why.

Laburnum

Pensive beauty,

Her golden boughs

Tumbling

Like warm summer rains.

Forsaken,

Her sunshine blooms

Shrouding

Poison in her veins.

Lethal enchantress,

She is resplendently

Captured

In her dazzling chains.

The second tree I remember clearly as a child was a very old pear tree that stood at the bottom of the garden. My childhood garden was long and backed onto some woodland leaving the bottom part of the garden feeling a bit spooky as it was rather shaded. The pear tree was incredibly tall, the tallest I’ve seen to date and I actually felt rather in awe of her height and rather intimidated by her, almost feeling as though she was watching.

Noble Pear

Noble pear,

Standing there,

Your gracefulness

Without compare.

Tall and proud,

Branches wide,

Laden with your

Female pride.

So many years,

So much seen,

You stand alone

As crone,

As Queen.

Another tree that really stood out to me as a child was in the garden of my grandmothers house in Kent. It too was very old as it was extremely tall. She was a splendid silver birch. At her base was a rockery and I used to sit here reading beneath the boughs of this wonderful tree. Sadly, she was uprooted in the great storm of October 1987 spanning across four gardens where she lay. The garden never looked the same without her there.

Lady of Grace

Lady of grace,

Your silvery wood,

A pioneering presence

When you once stood.

Enigmatic elegance,

Tall and slender,

Your purity shone

With perfect splendour.

Sorrow sprang

When your beauty fell,

For I was enchanted

By your fertile spell.

. It’s been wonderful revisiting these trees through visualisation, remembering their stories, the people that surrounded them and in hindsight the signs they were showing me and the lessons they taught which I am only just now learning about.

The laburnum taught me about the dangers of eating plants you know nothing of and that looks can be deceiving. The pear has been teaching me that not everything in the shadows is to be feared, a valuable lesson when working with the shadow self. She is also teaching me of age and wisdom and strength in the feminine. The silver birch is teaching me about death, loss, love and the cycle of life.

These are just a few I have honoured with poetry so far, there are many more trees that have related to during my life and I’m sure I will meet many more. It will be interesting to see where the journey into my memories of trees takes me.

earthmothernaturelover.wordpress.com

instagram.com/earthmothernaturelover

***

Robert Brothers (Bobcat) talks here about the wonderful things that can happen when we stop and listen to what the living world is telling us.

When the Ravens Called

The most beautiful spiritual experiences of my life happened the day after the Bear Dance, when a dancer and a singer came up in the snow on Mount Lassen with me. I wasn’t sure they would, but when I was driving out into the mountains, I saw a big white truck pull in behind me, wondered a bit, and then said, “Oh, It’s Dewey & Michelle!”

After driving for miles between tall Ponderosa Pines, the bark of the tall trees darkened and the foliage lowered, telling us we were now in the high elevation forest of Red Fir on the north slope of Mount Lassen: Kohn Yahmahnee, Snowy Mountain in the language of the Mountain Maidu.

On a blue sky sunny day, we went over the pass at 5900 ft and turned into a snow-covered pull-out across from the deep forest, trees covered with snow. I chose this place because it is on the ley line reaching straight as an arrow 160 miles from Mount Lassen to Mount Shasta to Mount Ashland to the ancient Salmon Ceremony site at Ti’lomikh Falls on the Rogue River. Known as Bobcat, a lone white man among Takelma Indians, this is where I was one of many helping Grandma Aggie bring back this traditional ritual of reciprocity. At the height of the first ceremony, we saw a Salmon leap bright red out of the water next to us in the side channel below the Falls, exactly when the pipe was lit.

When we began walking into the few inches of crunchy, new-fallen snow in the forest, before Michelle found the Bobcat tracks, drops of snow water found us, golden blinks of sunlight melting from the snow-covered treetops. They started and stopped while we were watching.

The Bobcat tracks led uphill towards a tall tree that a pair of Ravens led us to, a flat-topped snag where they landed, comfy in the calm air. They groomed each other, as loving couples do, and Dewey came up to join his partner by the tree. He offered a Raven song that he had just learned, his deep voice echoing loud through the forest, and the Ravens stayed to listen.

Later, when my friends had left and I started walking further uphill under the tall trees, the Ravens called. I looked up, and saw a bright white Snowy Owl gliding low above the treetops in the blue sky of broad daylight, looking right down at me.

We are known, not alone.

Revisiting these events now, 2 years later, a song eerily presaging them came back to me from Snow Blessing ceremonies 6 years ago. All I had to add was the last line.

When I saw the sun reflected in the snow coming down,

I felt so all-connected and I knew that I’d been found,

it was not what I expected when I heard that joyful sound,

Ravens calling me to see a Snowy Owl looking down.

This is what happens when we show up to where the critters call us to be.

******************************************

ISSUE 1: INDIGENOUS

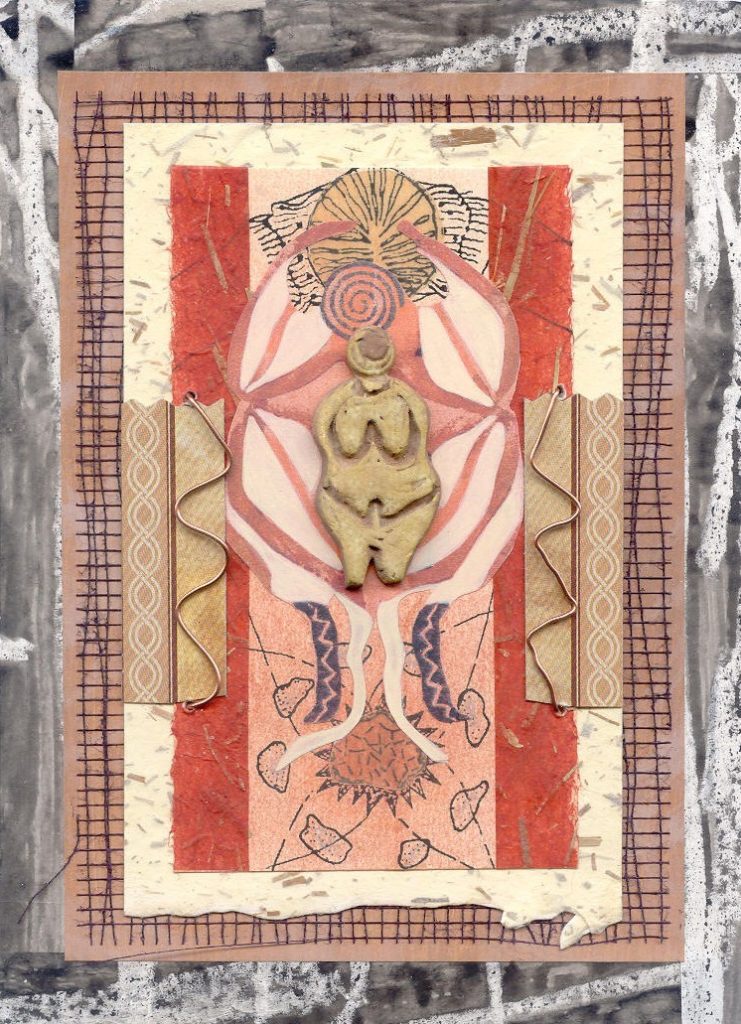

In this article, author and artist Pegi Eyers describes her experience of finding an authentic way of relating to the land as a person of Celtic descent in in her home of Ontario, Canada.

European Indigenous Knowledge: Finding My Way Home

The effort to protect Mother Earth is all of humanity’s responsibility, not just Indigenous people. Every human being has Ancestors that understood their umbilical cord to the Earth, and to always protect and thank Her. Therefore, all humanity has to re-connect to the Indigenous Roots of their own lineage, and to heal their connection and responsibility to Mother Earth. [1]

Chief Arvol Looking Horse, Keeper of the Sacred White Buffalo Calf Pipe (Lakota)

Everyone needs to get back to their own Indigenous Knowledge (IK). [2]

James Dumont, Anishnaabe Elder & Traditional Teacher,

5th Degree – Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge

Today, epic statements by Chief Arvol Looking Horse, James Dumont and other First Nations Elders, wisdom keepers and academics [3] are offering us a great blessing, with the implication that Indigeneity is the collective birthright of all humanity, and that we all have ancestral knowledge. Before the rise of monotheistic religions and techno-capitalism, all cultural groups were Indigenous, often matriarchal, and came from societies deeply connected to the land and the cycles of all life. At one time we all lived in tribal groups that acknowledged the sacred in every activity, and emphasized the bonds of the community over the cult of the individual. Our Indigenous world was perceived through our history, traditions and kinship groups, and we experienced deep relationships with the animals and the wild. We were comfortable in the natural world, and were in unity with the spirits, elementals, Ancestors and spiritual forces with whom we shared our lives. And yet, at some point in everyone’s history, Empire took hold and decimated our traditional, earth-connected way of life.

Today, we see that the drivers of manifest destiny and the myth of progress have created an illogical, unsustainable quagmire, destructive to all beings and ecosystems that share the planet. As societal problems worsen and environment degradation intensifies, we see that the dominant paradigm is unsustainable, and millions of us are waking up to the impossibility of continuing to believe in the imperialist lies of Empire. Our system of capitalism and endless growth is not compatible with the life-generating design and natural systems of the planet, and the sooner we come to terms with this, the better. The time has come to challenge the colonial legacy of domination, resource extraction, eco-fascism and corporatism, and to take responsibility for the fact that our society was created by an agenda of slavery, genocide and stolen land.

As we shake free of our colonial past, it is essential that we all become protectors of Mother Earth, to stop the destruction and plunder of what has become our ancestral lands as well. And as we actively move away from Empire and uncolonize, the original voices of First Nations – their history, narratives and experiences on the land – are of primary importance to us all. Beyond our urban cocoon we learn that Gaia is a four-season paradise, and that there are cultural groups who have lived on the land happily for millennia, and have survived and thrived and flourished. But more importantly, we learn that human beings are meant to honour the Earth in all we think, say and do, and that there is a better, more harmonious way for us to live, interconnected with the other-than-human world, and Earth Community.

Over many years, my experiences with growing close to the Anishnaabe – the Odawa, Algonquin and Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg cultures of my homeland in Ontario, Canada – has led to a valuable familiarity with their epic and enriching worldviews, all-encompassing and equivalent to any religious system in the world. As a cultural treasure, the sacred knowledge of the Anishnaabe is an irreplaceable part of the ethnosphere, the collective human legacy and the monumental web of cultural diversity on planet Earth. Through reading, dialogue, cultural events, ceremonies and personal relationships, I learned of Anishnaabe history, spirituality, colonization, resistance, protocol, decolonization and contemporary resurgence. And as part of my academic training in Fine Arts, and as a prequel to my career as a visual artist, independent curator and writer, I took college courses in Anishnaabe Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and Contemporary Issues in the Native World.

During the years that I participated in First Nations ceremonies and events as an invited guest, it was understandable that at other times my non-native presence was tenuous to the bridge-building dynamic. Although I mixed in at ceremonies, pow wows and cultural events, it never felt right for me to assume any kind of ownership over Anishnaabe tribal expressions. In my own developing sense and knowledge of the sacred, and in collaboration with both native and non-native people, I wore Indigenous jewellery, collected native art from First Nations artists, and made tobacco ties, medicine bags and a ceremonial drum. But ultimately, without a true connection to the communities from which they sprang, these forms or containers for cultural expression naturally and eventually fell away, in favor of Celtic Animism and ecomystic practices more authentic to me. Tobacco at the ready, and as much as the native person seemed to appreciate my offering, it was always an uneasy exchange. And rightly so. My blonde hair, blue eyes and pale skin placed me squarely in another knowledge system, hidden within the homogeneity of Canadian identity, and this remained a mystery both to myself and others for many years.

I will be eternally grateful to the traditional Anishnaabe for the knowledge that they graciously shared with me, and for the many gifts of insight and “good mind.” Teachings from the Elders, Indigenous artists, books, film, theatre, music, and my First Nation friends sparked my artistic and spiritual life for two decades. And as much as I developed a great deal of cultural sensitivity, I need to apologize to anyone who may have been offended by my unbounded enthusiasm for the beauty of earth-connected traditions. In retrospect, I now see that learning about the Indigenous cultures of Turtle Island enabled a wider opening of my own pre-colonial heart and soul, providing fertile ground for my own European Indigenous Knowledge (EIK) to flourish. My 20-year path spiralling through the periphery of the Anishnaabe world led to a significant kinship with the Curve Lake First Nation near Peterborough, Ontario, where I resided for three years. At the same time that I was experiencing the rewards of friendship and intercultural sharing, I was also feeling like an interloper, and that my First Nation friends and neighbours were entitled to a dedicated space free of colonial presence (me) for the much-needed revitalization of their cultural expressions. Right on cue (it seemed) I deepened my learning about racism, white privilege and allyship. This new information enlarged my picture of the Settler/First Nations interface dramatically, and shifted my journey of heart and mind to a more neoteric alignment. These days I do not presume to be welcome in First Nations spaces unless invited, and my only desire is to attend First Nations cultural events strong in my own ancestral traditions. It is interesting how this new cycle in my life coincided with the directive coming from Indian Country, that “everyone needs to get back to their own IK.”

“I leave behind the person I once was, who cared so deeply for so

many wonderful people, places and things, finding it was all dust.

Then, moving down the trail I am met by everyday magic,

as I stir my solitary dust into the sacred cauldron we call life.

Newly awakened, or waeccan,[4] to my Celtic roots,

kissed by the sun and blessed by the moon,

I am infused with an inexplicable desire to SPEAK OUT

~ on behalf of our Mother the Earth,

and all those who would live in harmony with Her.”

For the first time, I began to examine what my own Indigenous Knowledge would look like, as a person of European descent who had been displaced from my traditional homelands for eight generations. In 1832 my Scots Gael ancestors arrived to the lands and waters of the Anishnaabe – what is now called Simcoe County – and established the town of Orillia. How does a member of the European diaspora find re-indigenized roots and a true eco-consciousness in our adopted landscape of Turtle Island? The ambiguity of re-indigenizing on lands colonized by our own ancestors is a paradox not easily solved. But by virtue of our rootedness in our communities, our buried Ancestors, and our mutual love of the land, for better or worse both native and non-native people now share Turtle Island. And as much as we would wish it so, it may not be feasible for those of us in the diaspora to “decolonize” or return to our places of origin. One thing is clear – that in whatever form our cultural practices take, we are all working toward harmony and peace within ourselves and the world, and to love Indigenity with all our heart, mind and soul. It may not be too late to establish the peaceful co-existence that the colonial powers denied us all! Owning our white privilege, taking responsibility and activating a moral code can be our compass, as we navigate through the joys of spiritual ecology, and reclaim our original and authentic selves once again.

In my generation, spiritual seekers have been accustomed to accessing any belief system that we choose, through a panoply of New Age practices including Reiki, Shamanism, Buddhism, Yoga and many other modalities. In the past I had been immersed in some of these practices, but they began to feel fabricated and contrived. I was searching for the new/old pathways that would lead me back to my own ancestral lines in both Scotland and England, and indeed, I found many rich treasures in folklore, mythology, earth-honoring rituals, ceremony, plant-spirit medicine and other animist practices. The most astounding discovery was finding a direct line through my matriarchal mtDNA, to the cave-painting cultures of Lascaux in France 33,000 years ago. My search for ancestral roots and community is an ongoing process, and the joy of reclaiming and embodying my European Indigeneity continues to deepen. As diverse Indigenous societies and mystical traditions tell us, true knowledge is gained by thinking with both the heart and the head – a journey of emotion as informed by the mind – and my search for the Old Ways has been tempered by my true heart’s knowing, and the personal agency of that expression.

If one’s European Indigenous Knowledge has been lost to the mists of time, or the ancestral line is too difficult or painful to recover, the renaissance of belief systems such as Neo-Paganism and Druidry is good news indeed, and contemporary nature-based spiritualities such as Animism and Ecomysticism hold elements of both ancient and modern practice. There are a diversity of course-corrections for the contemporary spiritual seeker, and new ways to embody a genuine earth-connected path. What I found as I explored my own European Indigeneity, was that embracing pre-colonial, or ancestral thinking, was foundational to any attempt to revive ethnoculture(s). Shifting away from western and colonial thinking is key! For all of our alliances and relationships, uncolonization insists that we understand ourselves as pre-colonial people, and that by implementing ancient themes and ideals we can adopt holistic solutions and build earth-connected community once again.

IK/EIK systems found all over the world are irreplaceable, and need to be rejuvenated and protected. IK/EIK embodies the wisdom and understanding that is accumulated over thousands of years, and provides alternative models to Empire and domination. There are no universal laws governing the diverse forms of IK/EIK found worldwide, but earth-honoring cultures do share common values. Alternative definitions or terms for IK/EIK may include “animist folk traditions,” “ecological science,” “land-emergent knowledge,” ancestral wisdom, ancestral wisdom teachings, ancestral knowledge, ancestral pathways, “folk knowledge” and local wisdom. Informed by my own personal land-based knowledge, I was able to compile a collection of IK/EIK tenets and lifeways drawn from ancient origins, including those that most certainly were (and still are) found in the wide range of EIK and Pagan traditions of Old Europe, plus Celtic Reconstructionism (CR), Nordic Paganism and Matriarchal Studies. Here are a few samples from that extensive list:

- The Earth is the Sacred Mother of All, the source of all life and joy. We honour our blessed Gaia and support the interconnected web of life that sustains us all.

- The world is a place of sacred mystery, and our relationship with the world is rooted in a profound respect for the land and all life. Humans are not above creation but part of it, and we flourish within the boundaries of the Sacred Circle.

- When we fully recognize the interconnectivity of all creation, we acknowledge that it is the responsibility of human beings to use our agency to enrich and protect the sacred web, especially the life-giving elements of water, earth and air. We have a love and reverence for all life, and a balanced and harmonious relationship with the Earth.

- At the heart of the epistemology of all IK/EIK systems is the recognition that human beings need the water, plants and animals to live, and that the water supply, food forest, and predator/prey relationship is essential to all life. This fundamental sacred dynamic is approached with great propriety, humility, gratitude, respect, protocol, care and ceremony. The ability to stay within natural limits and in a symbiotic relationship with the ecosystems of the planet represents the height of human intelligence and sophistication, and there is absolutely nothing in the belief systems, achievements, or technologies of misguided humancentric western civilization that even comes close to this pre-eminence.

- All human culture arises or is informed by the land, from our bond to a particular landscape, and we are connected to the climate, beings, deities and spirits that dwell there. Our very blood and DNA is tied to our ancestral lands, and we are rooted in place, inseparable from our homelands, deeply linked to the sacred places that are the source of our origin stories, folklore and myths. The love of the land and our tribal group is the only true wealth we have – we are part of the Earth and the Earth is part of us.

- Our IK/EIK is an ancient, communal, holistic and spiritual wisdom that encompasses every aspect of human existence. Gathered over many eons, our oral tradition covers a canon of themes rich in mystery and power, in which complex interactions are encouraged between humans, animals, greenery, spirit beings, ancient energies, deities and the elementals in the natural world. Our origin, creation and migration stories are deeply embedded in the land, follow natural law, and hold the keystones to our traditions and cultural meanings. At the heart of our worldviews are narratives of emergence that outline our arising from the weave of nature, our interconnectivity with the sacred elements of earth, water, fire and air, and the beings that populate the more-than-human world.

- Our existence is sustained by expressions of gratitude such as prayer, ceremony, meditation and fasting, as we unconditionally give thanks for all life and the elements that make life possible. We are in a symbiotic relationship with the Earth, as everything we need to live a Good Life comes from the land, and our activities are intertwined with the cycles and seasons of nature. When we embody these principles and have respect for all beings through ceremony and prayer, the cosmic balance is upheld and restored, and the survival of the community ongoing.

- We honour the life-creating power of the Sacred Feminine and the women in our culture as an extension of the miraculous divinity of creation. Women are revered, and their fertility, procreative and nurturing abilities are known to be exactly the same as the Creatrix, chalice, crucible or cosmic womb that exists at the center of the universe. The inviolate nature and wholeness of women allows them to be exempt from tribal methods of spiritual seeking, petitions, initiations such as the “vision quest,” or sweatlodge renewal. In traditional and modern matriarchies or egalitarian societies, our IK teaches us to embrace the naturalness of physical contact in raising our children, and in expressions of familial, friendly or passionate love. We are well aware that human beings are designed in every way for the enhanced physical, spiritual and emotional wellness that comes from physical contact. We are at one with the mysteries and capabilities of our bodies, with nudity, with touching, with closeness, with intimacy, with sexual expression, with movement, with posture, with exercise, with pain, with illness, with aging, with dying, and all the natural manifestations and expressions of our physical bodies, the ground of our being. Women’s Mysteries are a sacred and respected part of the IK/EIK held communally by the tribe.

- We revere and honour our Ancestors, the trustees of the Earth, and our offerings and altars enable us to feel their presence, connect us to our original culture and place of origin, and preserve our heritage. Those who have gone before have established the traditions that guide us, and their bloodlines and genetic material have created us. There is no greater continuity to our IK/EIK memory and oral tradition, both individually and collectively, than communing with the ancient wisdom of our Ancestral Spirits. With gratitude we call upon them to teach us and show us the way, and we understand that in the greater continuum of time we are the Ancestors of the future.

For it is those of us that celebrate and practice Indigeneity in ourselves and others, in however authentic form that may take, that are the best hope for humanity. There is no predicting what shape this new-found collective will take in future, but if we do not believe that we have common ground in our mutual love for the land and our own IK/EIK, and that it is possible to embody cultural tolerance, peaceful co-existence, compassion and respect, then we perpetuate the Great Forgetting. By returning to our earth-rooted belief systems and reclaiming our Indigenous selves, we simultaneously reintegrate ourselves with the rest of humanity. We all have a place in the Indigenous Circle, and the ability to love all people as we love ourselves, as we value our Unity in Diversity. The Earth is a sacred magical place, all beings are a perfect manifestation of the Creatrix or Creator principle of the universe, and each human life is a miracle and a mystery.

NOTES

[1] Statement in solidarity with Idle No More by Chief Arvol Looking Horse (Lakota), NDN News – Daily Headlines in Indian Country, December, 2012

[2] James Dumont (Anishnaabe), “Introductory Remarks,” Elders and Traditional Peoples Gathering, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, February, 2010

[3] Pegi Eyers, “First Nations on Ancestral Connection” Ancient Spirit Rising Blog, Stone Circle Press, December, 2015 LINK

[4] “Waeccan” or “to be awake” in Old English simply means to be in tune with the presence of the mystery in nature, and I use it to align with my earth-wise Ancestors. When we are waeccan, our heart, mind and soul are open to the beauty in ourselves, and all of creation.

Pegi Eyers is the author of Ancient Spirit Rising: Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community, a survey on the interface between Turtle Island First Nations and the Settler Society, social justice work, sacred land, nature spirituality, earth-emergent healing, and the holistic principles of sustainable living. She is a member of the mtDNA-based Helena Clan (descended from Mitochondrial Eve as traced by The Seven Daughters of Eve), with more recent roots connecting her to the mythic arts of England and Scotland. Pegi self-identifies as a Celtic Animist, and is an advocate for the recovery of authentic ancestral wisdom and traditions for all people. She lives in the countryside on the outskirts of Nogojiwanong in Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg territory (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada), on a hilltop with views reaching for miles in all directions.

****************************

In this short personal memoir, Charlotte Graham Hjorth from the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids talks movingly about her experience of transplanting from Scotland to Sweden, and how she managed to find Home in a completely new place.

Transplanting

I am Scottish. I don’t know how much you know about Scottish people but I am one of those Scots that’s a bit weathered and wild and uncombed. Woolly jumper and wellies kind of Scot. Stand at the edge of the Atlantic and get slapped in the face with salt wind Scot. Scottish people like me are woven into the landscape, rooted to the rocks like heather and sturdy as a thistle. Yet at the age of 21, bruised and battered by poverty, abuse, and addiction I uprooted myself and relocated to Sweden. I was running to the man I love, but also fleeing the land which had formed me. I was faced with the reality of being ungrounded, in a place that I wasn’t altogether sure wanted me there. I was an outsider not only amongst people but in the birch forests and archipelagos that were so unlike the glens and lochs I was raised on. The earth feels different here; quieter, deeper, calmer. My wild spirit seemed to rattle the bones of the trees and offend the peace of the lakes. Every winter the world turned white and silent and frozen. Closed and asleep and unwelcoming. Every summer it was dry and still and languid like an overfed old man wanting to be left alone to get on with doing absolutely nothing. How could I ever put down roots, when the soil I trod upon seemed determined to resist my invasion?

My material situation stabilised, and I used this newfound security to go back to Scotland as often as I could. During these visits I would draw out as much as I could from the land, filling myself to the brim and hoping the recharge would last till the next visit. During my very last visit before the pandemic I climbed Arthur’s Seat in the howling rain. A pair of squawking corvids accompanied me part of the way until the weather became too bad even for them. At the top I shared the summit with a single, soggy tourist and looked out to the Firth of Forth. Everything beyond was shrouded in rain clouds. Now Arthur’s Seat is no mountain, but it is enough of a hill that I lamented for the umpteenth time the lack of anything remotely resembling a hill in the dense, flat forests of central Sweden. Don’t get me wrong, Sweden is a lovely place, but it just isn’t Scotland. This, this windswept little rock at the mouth of the North Sea, this was alive in a way that the lazy, frozen Baltic just couldn’t compare with. Here was life, and vitality, and the elements in their full, raw glory!

My overly romantic inner ramblings were at this point interrupted by the soggy tourist who wondered in his very broken English, if I could possibly take a picture for him now the rain had died down. I obliged and after several attempts I had provided a suitably presentable proof for him to take home. As he turned to leave his parting words, though delivered cheerfully, hit me harder than any bluster:

“It’s lovely here, but there is no peace!”

No peace. No, there wasn’t, was there? And as long as I stood here in the rain wishing Sweden was more Scottish then there would never be any peace for me. There was all of a sudden a sense of finality in this excursion. Though I didn’t know it yet, the pandemic was just around the corner and this would be my last trip to Scotland for many years to come. Despite this, I knew that something had shifted, and pandemic or no, a seed had been planted which would soon flourish in the sleepy little corner of Scandinavia I inhabited.

Soon after my return to Sweden, we took a family trip to a Viking age burial ground. Not far from the burial site there is a small forest, and in that forest, there is a labyrinth. It is barely visible under the grass, but if you look carefully, you can see it well enough. There is a sign beside it telling visitors how it is believed the grove in which we stood was sacred to the pre-Christians who lived nearby and that the labyrinth was most likely ceremonial in use. I carefully picked my way through the stones, winding and doubling back and wondering. I was half holding my breath, waiting to see what would happen when I reached the centre. It may sound disappointing, but nothing much happened at all, and I rather think that was the point. There was no great sundering moment of enlightenment, but instead a calm stillness, tinged with gentle acceptance. Mosquitos buzzed and a small bird rustled through the undergrowth. Nothing happened but at the same time, everything changed. Have you ever seen a litter of kittens sleeping? A sibling will slip into the basket and the little huddles of furs will rearrange itself without a fuss to accommodate the arrival. It was so I entered into the spirit of the land, without fuss or hullabaloo. It simply shifted to allowed me to slip into the warmth of acceptance and peace.

I have come to understand the land I live in so much more since then. The energy here is no less powerful than Scotland, but it moves differently. It is stoic and reliable. It invites you to stop, take off your jacket and sit with it for a bit. It will gently whisper its secrets to you, if you are inclined to listen with patience. The earth will always want to speak to us, but its voices are as varied as the many languages around the globe. It took me many years to learn to hear the voice of the earth here, but it was a lesson that needed to be learned slowly, carefully and completely. I have been transplanted here, and now it would seem that my roots have finally taken hold.

CHARLOTTE GRAHAM HJORTH, 2023